Some Background

Recently at work I faced an interesting challenge while implementing a new feature. When users load up a new instance of our app, the app scans

their input data and then generates a series of default values that are stored in a state object. Elements like height, color, order, and labeling

are all pieces of state that can be updated, saved, imported, and exported. Users can also supply their own state data to be used in lieu of the defaults,

and users can have any number of different states associated with each project. The challenge - allow users to supply incomplete state data, and have the app

fill in the blanks without overriding the user’s data. For the solution, let’s head to the cat circus!

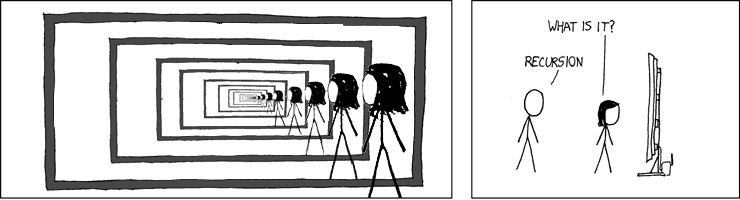

Why Recursion

One of the goals of good software is extensibility - instead of writing a function to greet Paul, we’d want to write a function that can greet anyone, and takes in a name (or better yet, any number of names) and greets each of them programmatically. Similarly, when dealing with deeply nested data it becomes incredibly cumbersome to hardcode processes. Maybe the object structure changes, or levels are added/removed, and your hardcoded solution no longer works. Distilled to its most basic form, a recursive function does something until a specific condition is met, and then it stops (or does something else). Like hunting for buried treasure - you dig a hole straight down until you hit a treasure chest, and then you stop.

The Scenario

The cat circus is in town, and you and a friend managed to snag tickets to opening night! You both arrive early and take your seats, notepads in hand - ready to log everything you see during the show. But there’s one thing neither of you accounted for - these cats are fast!

So fast and mesmerizing is the action that you’re unable to jot it all down in time. Each time you look up from your notebook, a brand new cat with a brand new skill has been introduced, and you’re barely keeping up. After the final act ends and all the cats come out to take a bow, you take a look at your notes and realized you may have missed some action.

let catCircus = {

actOne : {

01 : {

name : 'Holly',

age : 7,

act : 'spun a plate on her head',

crowdReaction : {

start : 'polite applause',

finish : 'frenzied clapping'

}

},

02 : {

age : 2,

act : 'can write in cursive'

},

03 : {},

04 : {

name : 'Mr. Shoeshine',

crowdReaction : {

finish : 'they stormed the stage'

}

},

},

actTwo : {

...continued

},

}

You glance over to your friend who looks up from their own notebook, similarly crestfallen. The bad news - you were both suckered in by the wildly cute and entertaining cats, and your notes reflect your distraction. The good news - between the two of you, you’re confident you’ve captured a complete dataset. You run out of the auditorium (after buying a shirt) and head straight to your computer. You’re going to write an algorithm that takes in both of your incomplete datasets and spits out a complete one. And since the dog frisbee throw competition is in town next week you’re going to make sure your algorithm is extensible, so you can kick back and enjoy those frisbee pups. As you load up your IDE and settle your fingers onto the keyboard, you begin by framing out how your algorithm should work. You know that it should probably

- take in two datasets

- return either dataset if both datasets are the same (in this scenario, this implies they’re both complete)

- iterate through each layer of the first dataset. At each point, account for the following

- if we’re not dealing with an object, return

- if the key/value pair for set A === set B, do nothing

- if the kvp for set A does not exist in set B, add it

- if the kvp for set A !== set B, we recurse!

- once we’ve iterated through the deepested nested values, we can repeat the process by flipping the datasets

Great, you’re ready to write some code! Let’s start with a helper function that ensures we’re dealing with objects.

compareDatasets = (a, b) => {

isObject = item => typeof item === 'object' ? true : false // check and end recursion if not provided an object

}

Now you’re ready to start iterating

compareDatasets = (a,b) => {

isObject = item => typeof item === 'object' ? true : false // check and end recursion if not provided an object

if(isObject(a)){

Object.entries(a).forEach(([key, value]) => {

if(a[key] === b[key]){ // if kvp in dataset a === dataset b, do nothing

return

} else if(b[key] == null || b[key] == undefined){ // if dataset b is missing an element found in dataset a, add it

b[key] = value

} else if (b[key] !== value){ // the objects don't match, so we recurse down a level

compareDatasets(a[key], b[key])

}

})

}

}

And once you’ve gone through the first dataset, you can repeat the process for the second! You can keep your function DRY by creating a ‘parent’ function that calls compareDatasets()

compareDatasets = (a,b) => {

isObject = item => typeof item === 'object' ? true : false // check and end recursion if not provided an object

if(isObject(a)){

Object.entries(a).forEach(([key, value]) => {

if(a[key] === b[key]){ // if kvp in dataset a === dataset b, do nothing

return

} else if(b[key] == null || b[key] == undefined){ // if dataset b is missing an element found in dataset a, add it

b[key] = value

} else if (b[key] !== value){ // the objects don't match, so we recurse down a level

compareDatasets(a[key], b[key])

}

})

}

}

animalEventNotesGenerator = (a,b) => {

if (a === b) return a // if they're the same, return

compareDatasets(a,b) // compare a to b

compareDatasets(b,a) // compare b to a

return a // return a complete dataset

}

Now anytime you and your buddy go to enjoy some amazing animal-based spectacle, you can rest easy knowing you’ll be able to get your notes together with a couple quick clicks. All those programming

lessons are finally paying off :)